As woodworkers, we often obsess over our tools. We debate the merits of bevel-up versus bevel-down planes, we argue about table saw horsepower, and we spend hours sharpening chisels until they can split a hair. But the most important element in the workshop isn’t the steel in your hand; it’s the material on your bench.

To truly master woodworking, you must stop looking at a board as an inert slab of material and start seeing it for what it truly is: a bundle of once-living cells that spent decades or centuries reacting to the sun, wind, rain, and soil.

Understanding the biology of a tree doesn’t just make you a dendrologist; it makes you a better craftsman. It tells you why a board warps, why it splits when nailed near the end, why it absorbs stain unevenly, and why some woods polish to a glass-like shine while others feel coarse no matter how much you sand.

In this deep dive, we are going to explore the anatomy of wood—from the microscopic cells that hold it together to the macroscopic growth rings that tell its history.

The Two Great Families: Softwoods vs. Hardwoods

Before we cut into the wood, we have to classify it. The most common point of confusion for new woodworkers is the distinction between softwood and hardwood.

It seems intuitive that these terms refer to physical density. However, this is a biological classification, not a mechanical one. Balsa wood is biologically a hardwood, yet it is softer than almost any softwood. Yew is biologically a softwood, yet it is harder than many hardwoods.

The difference lies in reproduction (the seeds) and the leaves.

Gymnosperms (Softwoods)

These are the conifers, or “needle-leaved” trees (Pine, Fir, Spruce, Cedar).

The Wood: generally lighter in weight (though not always) and often resinous.

The Science: They belong to the group Gymnospermae (“naked seed”). Their seeds usually fall from cones.

The Structure: Softwoods have a primitive, simple cell structure. They are evolved for efficiency in colder or harsher climates.

Angiosperms (Hardwoods)

These are the broad-leaved trees (Oak, Maple, Walnut, Cherry). Most are deciduous (losing leaves in autumn), though some tropical hardwoods are evergreen.

- The Science: They belong to the group Angiospermae (“vessel seed”). Their seeds are enclosed within a fruit or a nut (like an acorn or a walnut).

- The Structure: Hardwoods possess a complex cellular architecture.

- The Wood: generally denser, more varied in color and figure, and lacking the resin canals found in pine.

Woodworking Takeaway: Don’t assume a wood is durable just because it is classified as a “hardwood.” Always check the specific Janka hardness rating of the species you are using.

Inside the Wood — Cellular Architecture

If you were to look at a block of wood under a powerful microscope, you wouldn’t see a solid mass. You would see a bundle of long, tubular cells running longitudinally with the trunk.

Think of a tree trunk as a handful of drinking straws packed tightly together, held in place by glue.

- The Straws (Cellulose): The cells are primarily composed of cellulose. These provide the tensile strength of the tree.

- The Glue (Lignin): The cells are bonded together by an organic chemical called lignin. Lignin is rigid and acts like the concrete to the cellulose’s rebar.

This orientation creates grain. When you run your hand along the board and it feels smooth, you are sliding over the length of the “straws.” When you run your hand the other way and it feels rough or splinters, you are catching the open ends of those straws.

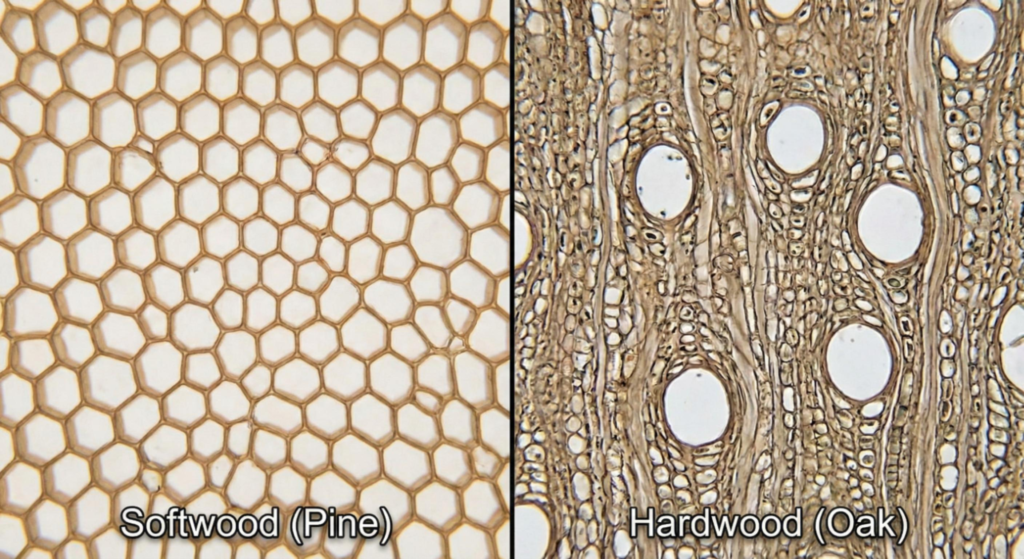

The Structural Difference: Pores vs. Tracheids

This is where the difference between Softwood and Hardwood becomes vital for finishing.

1. Softwood Structure (The Simple System)

Softwoods are comprised of about 90% tracheids. These are long, fiber-like cells that do double-duty: they provide physical support for the tree and conduct sap. Because the cells are uniform, softwoods are often described as having a “closed grain” or a uniform texture.

2. Hardwood Structure (The Specialized System)

Hardwoods evolved later and developed specialized cells.

- Fibers: Thick-walled cells that provide support but do not transport fluids.

- Vessels (Pores): Large, open tubes specifically designed to transport sap.

Because hardwoods have these large vessel pores, they can have a “coarse” texture. If you look closely at the end grain of Red Oak, you can actually see the holes (pores) with your naked eye.

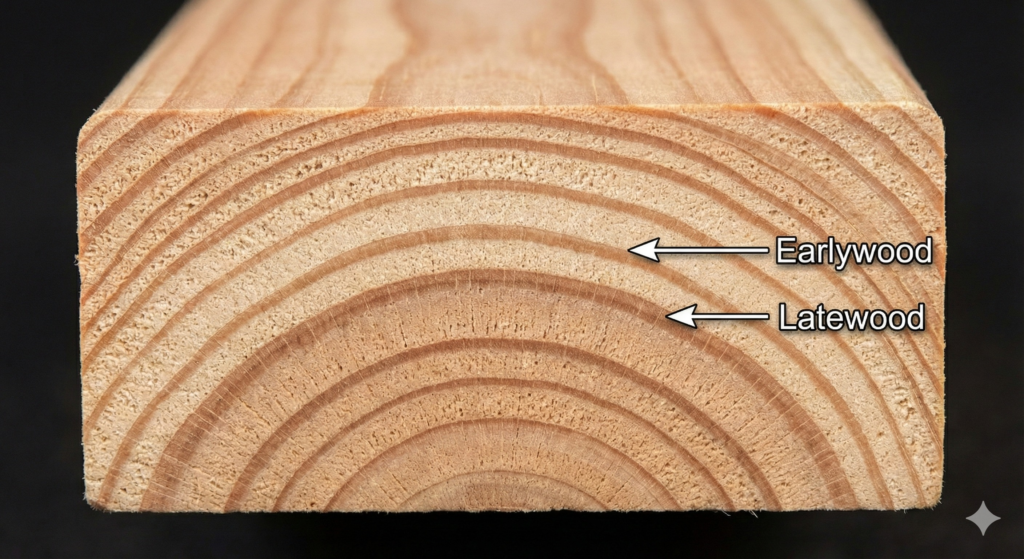

Reading the Rings

Earlywood and Latewood A tree grows by adding a new layer of wood on the outside of its trunk every year. This happens at the Cambium layer, a thin zone of living reproductive cells located just beneath the bark. However, the tree does not grow at the same speed all year round. This variation creates the distinct banding we see as “Growth Rings” or “Annual Rings.”

The Spring Rush: Earlywood

In the spring, the tree wakes from dormancy. It needs to move massive amounts of sap to the budding leaves to jumpstart photosynthesis. The cambium produces cells that are:

- Large in diameter.

- Thin-walled.

- Lighter in color.

This band of wood is called Earlywood (or Springwood). It is porous and relatively soft.

The Summer Slowdown: Latewood

As summer progresses, growth slows. The tree shifts focus from fluid transport to structural stability to survive the coming winter. The cambium produces cells that are:

- Small in diameter.

- Thick-walled.

- Darker and denser.

This band is called Latewood (or Summerwood).

Why This Matters to Your Sanding Block

The alternation between soft Earlywood and hard Latewood creates a challenge. If you are sanding a species with distinct rings (like Fir or Ash) using a soft backing pad, the sandpaper will eat away the soft Earlywood faster than the hard Latewood.

The result? A “washboard” or corrugated texture.

Pro Tip: When sanding woods with prominent grain contrast, use a hard sanding block. This bridges the gaps and forces the abrasive to cut the hard Latewood level with the soft Earlywood.

Texture and Distribution

Ring-Porous vs. Diffuse-Porous

Not all hardwoods arrange their pores the same way. This distribution dictates how you finish the wood.

1. Ring-Porous Woods (e.g., Oak, Ash, Elm)

These trees lay down massive pores in the spring (Earlywood) and very tight fibers in the summer. This creates distinct, visible rings.

- Finishing implications: These woods have a “texture” you can feel. If you want a glass-smooth table top with Oak, you often need to use a “pore filler” or “grain filler” paste to fill the valleys before applying your topcoat.

2. Diffuse-Porous Woods (e.g., Maple, Cherry, Beech)

These trees distribute their pores evenly throughout the growing season. The pores are usually too small to see without magnification.

Finishing implications: These woods sand to a very smooth, consistent surface and rarely require grain filling. However, because the surface is so uniform, they show sanding scratches much more easily than ring-porous woods.

Heartwood vs. Sapwood

The Core of the Tree

If you look at the cross-section of a log (like Walnut or Cherry), you will usually see a lighter ring of wood on the outside and a darker, richer core. This is the difference between Sapwood and Heartwood.

The Lifecycle of Sapwood

All wood starts as Sapwood. This is the living (or partially living) wood near the outside of the trunk. Its job is to conduct water and store food (starches/carbohydrates).

- Characteristics: Lighter color, high moisture content, permeable.

The Transformation to Heartwood

As the tree grows in girth, the inner sapwood gets farther from the active bark. The tree no longer needs these inner cells for conduction. It “retires” them.

Through a chemical conversion process, the tree pumps these old cells full of extractives—tannins, oils, resins, and gums. This blocks the pores and kills the cells. This dead, chemically treated core is Heartwood.

The Comparison

For the woodworker, the distinction is vital. Here is how they compare:

| Feature | Sapwood | Heartwood |

| Color | Pale, white, or cream. Often looks “washed out.” | Darker, richer. Contains the hues we associate with the species (e.g., the purple/brown of Walnut). |

| Function | Conducts sap and stores food. | Structural support (the spine of the tree). |

| Durability | Low. Prone to fungal decay and beetle attack because it is full of tasty sugars and starches. | High. The extractives (tannins/oils) act as natural fungicides and insecticides. |

| Moisture | Porous; gives up and takes on moisture quickly. | Denser and less permeable; more stable. |

| Finishing | Absorbs stain “greedily” and often unevenly. | Absorbs stain consistently; harder to impregnate with preservatives. |

Should you use Sapwood? In traditional furniture making, sapwood is often cut off and discarded (or used for secondary parts like drawer sides). It is considered a “defect” because it rots easily and doesn’t match the color of the heartwood. However, in modern woodworking, many makers embrace the contrast, using the creamy sapwood to highlight the live edge of a slab.

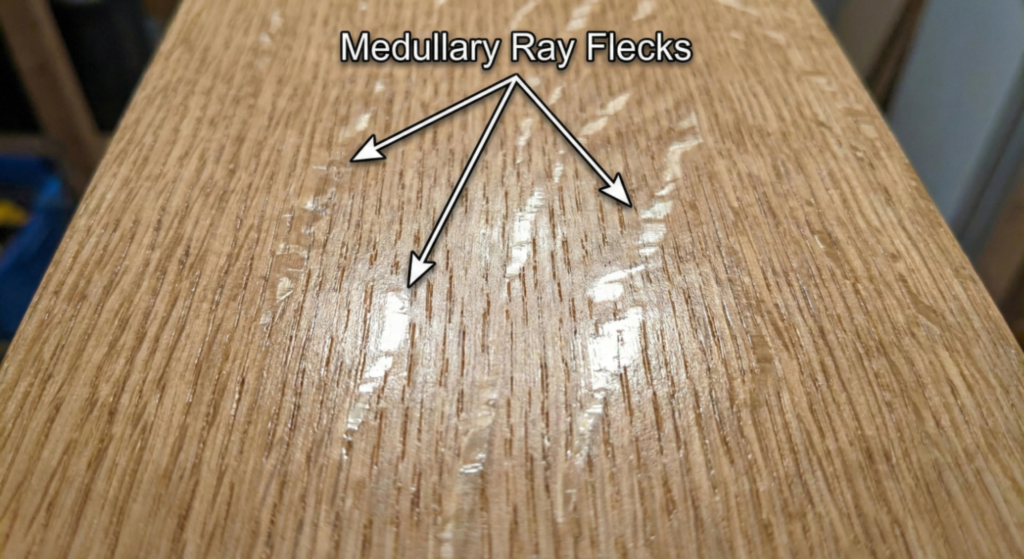

The Ray Cells

The Horizontal Traveler

We’ve established that most wood cells run up and down the trunk (longitudinally). But if that were the only structure, how would nutrients get from the bark into the center of the tree? Enter the Medullary Rays.

These are ribbons of cells that run horizontally from the center of the tree out toward the bark, like the spokes of a wheel.

- In Softwoods: Rays are very fine and barely visible.

- In Hardwoods: Rays vary in size. In woods like Beech or Oak, they are substantial.

The “Fleck” Effect:

When you cut a board “Quarter Sawn” (cutting perpendicular to the rings), you slice through these rays at an angle that reveals them as shiny flakes or ribbons. This is the famous “fleck” or “tiger stripe” seen in Arts and Crafts style Oak furniture. Those shiny spots are the ray cells reflecting light differently than the surrounding vertical fibers.

Conclusion: Working with Life

When you run a board through a planer, you aren’t just smoothing a surface. You are revealing the history of a living thing.

- That hard patch that resisted your sanding? That was a hot, dry summer where the tree grew dense Latewood.

- That sudden change in grain direction? That was where a branch once grew.

- The rich color you are oiling? Those are the chemical extractives the tree created to protect its heart.

By understanding the anatomy of grain, cells, and growth rings, you stop fighting the wood and start working with it. You learn to read the rings, anticipate the texture, and utilize the natural beauty of the tree’s biology.