Welcome To Part 4 Of Our 5 Part Series, The Woodworker’s Eye: From Concept to Creation

You’ve defined the function, ensured the structure, and drawn the plans. Now, you stand before a rack of lumber, and the real world intrudes. Your design is no longer an abstract concept; it needs to be made of something.

Choosing the right wood is one of the most critical decisions in the design process. The material you select will dictate not only the final look of your project but also its strength, durability, and how it behaves over time. A brilliant design can be ruined by the wrong wood, while a simple design can be elevated to art by the perfect board.

In this post, we’ll move beyond “it looks nice” and explore the practical and aesthetic considerations of selecting lumber. We’ll cover the difference between hardwoods and softwoods, the undeniable reality of wood movement, and how to use grain as a design element.

1. Hardwood vs. Softwood: It’s Not About Hardness

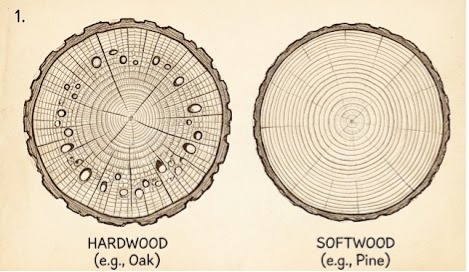

The first distinction you’ll encounter is between hardwoods and softwoods. It’s a common misconception that this refers to the actual hardness of the wood. In reality, it’s a botanical classification.

- Hardwoods come from deciduous trees (trees that lose their leaves in the fall, like oak, maple, walnut, and cherry). These woods typically have a more complex cell structure with pores and are generally denser and more durable. They are the preferred choice for fine furniture, cabinetry, and flooring because they can withstand daily wear and tear and take a beautiful finish.

- Softwoods come from coniferous trees (trees with needles and cones, like pine, cedar, fir, and spruce). They have a simpler cell structure and are often—but not always—softer and lighter. Softwoods are commonly used for construction framing, outdoor projects (due to natural rot resistance in some species like cedar), and painted furniture.

Design Tip: For a dining table that will see years of use, choose a durable hardwood like white oak. For a rustic outdoor bench, a softwood like cedar is a great choice.

2. The Living Material: Understanding Wood Movement

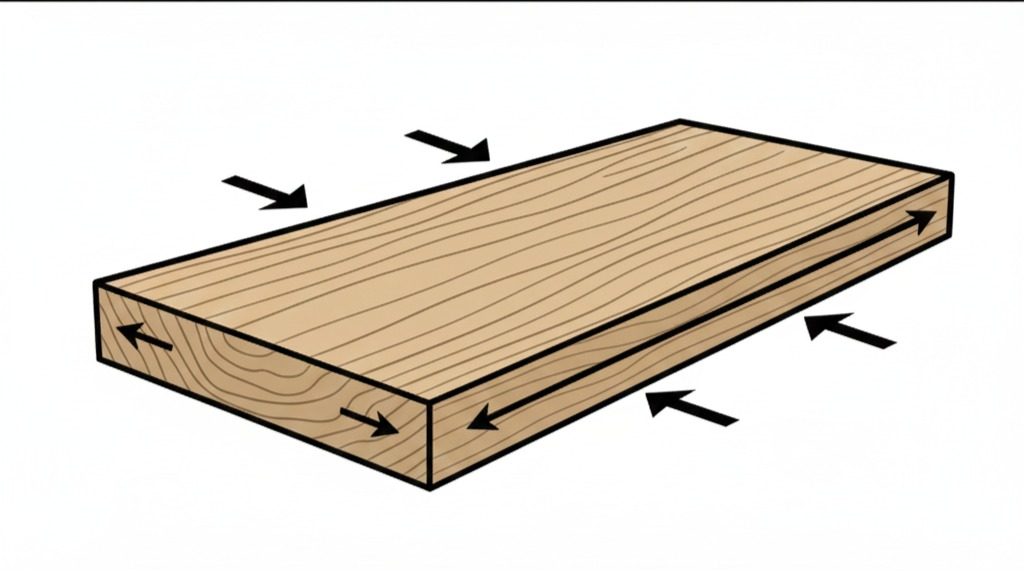

Wood is a hygroscopic material, meaning it acts like a sponge, absorbing and releasing moisture from the surrounding air. As it does this, it expands and contracts. This is a fundamental property of wood that you cannot ignore.

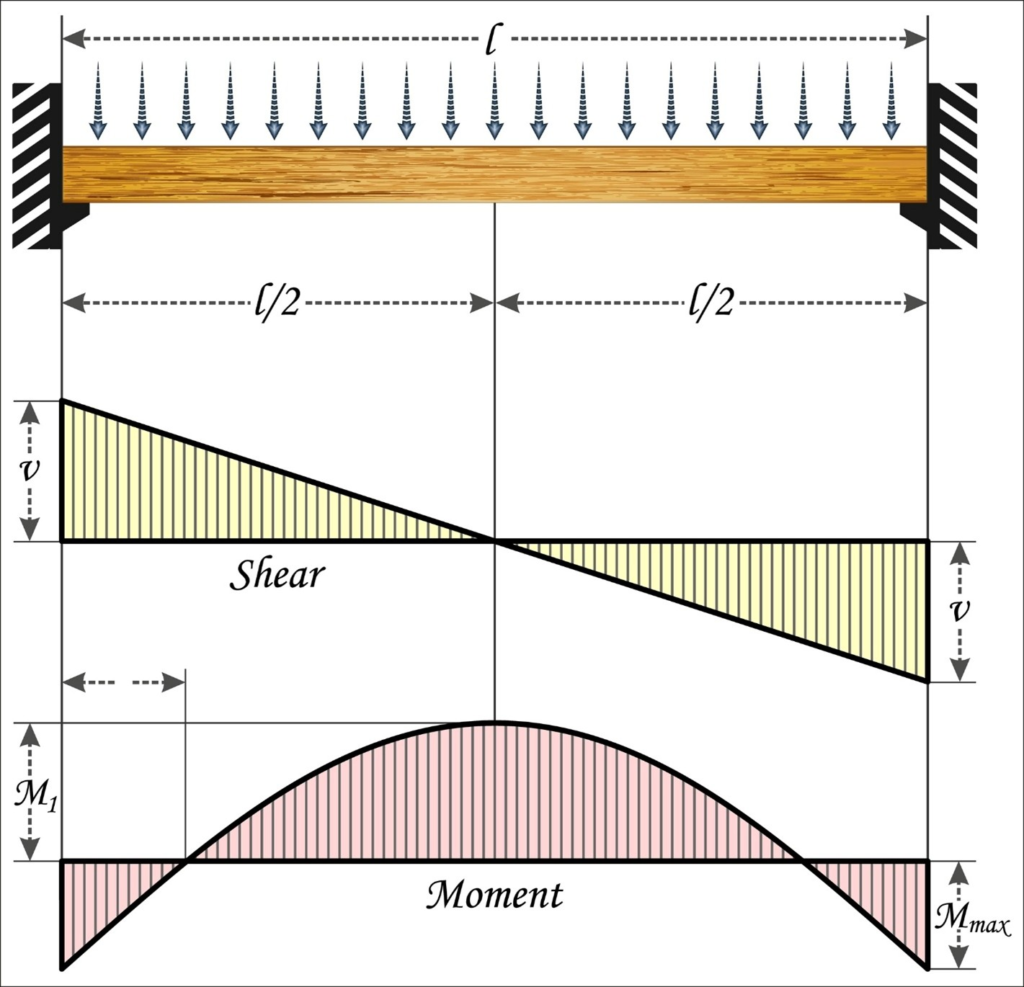

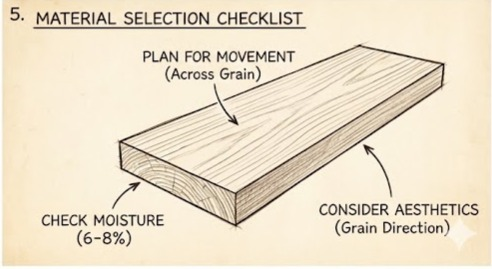

The crucial thing to remember is that wood moves significantly across the grain (in width) but very little along the grain (in length).

If you design a piece of furniture that constricts this movement—for example, by gluing a breadboard end firmly across the end of a wide tabletop—the wood will crack as it tries to expand or contract. Your design must allow the wood to “breathe.”

Design Tip: When designing a tabletop or a cabinet door, always consider how it will be attached to allow for seasonal movement across its width.

3. Moisture Content & Acclimation: Patience Pays Off

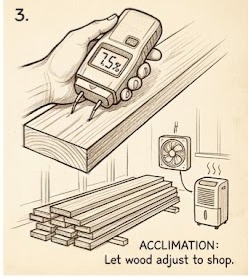

Because wood moves with moisture, it’s vital to know the moisture content of your lumber before you start building. Wood that is too wet when you build with it will shrink and crack as it dries in your home. Wood that is too dry might swell and warp in a humid environment.

Because wood moves with moisture, it’s vital to know the moisture content of your lumber before you start building. Wood that is too wet when you build with it will shrink and crack as it dries in your home. Wood that is too dry might swell and warp in a humid environment.

For indoor furniture, you generally want a moisture content between 6% and 8%. You can measure this with a simple, inexpensive tool called a moisture meter.

Before you make your first cut, let your lumber acclimate to the environment where it will be worked and eventually live. Stack it in your shop with stickers (small spacers) between the boards to allow air to circulate freely for at least a few weeks. This allows the wood to reach equilibrium with the shop’s humidity, minimizing surprises later.

Design Tip: Invest in a moisture meter. It’s a small price to pay to prevent a ruined project.

4. Aesthetics: Grain and Texture as Design Elements

Once you’ve addressed the practicalities, you can consider the aesthetics. The visual characteristics of wood—its color, grain pattern, and texture—are powerful design tools.

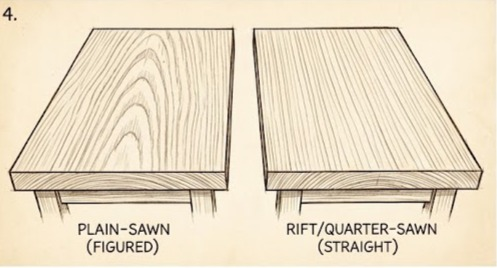

Grain Pattern: The way a log is cut at the mill determines the grain pattern on the board’s face.

Plain-Sawn: Produces cathedral or arching grain patterns. It’s the most common and economical cut, offering a more rustic or figured look.

Rift-Sawn & Quarter-Sawn: Produces straight, uniform grain lines. These cuts are more stable and are often preferred for a clean, modern look or for parts like table legs where you want consistent grain on all sides.

Texture & Figure: Some woods have a fine, uniform texture (like maple), while others are coarse and open-pored (like oak). “Figure” refers to distinctive patterns like curls, tiger stripes, or bird’s-eye, which can be used to create a stunning focal point.

Design Tip: Use grain direction to guide the eye and highlight the form of your piece. A long, straight grain can make a table look longer and more elegant.

Conclusion

Choosing the right wood is a balancing act between function, stability, and aesthetics. By understanding the properties of your material, you can make informed decisions that will ensure your project is not only beautiful but also built to last. Use the checklist in the final illustration as a guide before you buy your next board.

In the next and final post of this series, we’ll cover the essential tools you need to bring your design to life and the safety protocols that will keep you woodworking for years to come.