Welcome To To Part 1 Of Our 5 Part Series. The Woodworker’s Eye: From Concept to Creation

Every woodworker faces the same dilemma at some point: you’ve got premium lumber, a well-equipped shop, and an eagerness to create something remarkable. The temptation is to dive right in. But rushing past the planning stage is a mistake that even experienced makers occasionally fall into.

Form Follows Function: Why the Best Design Starts with “Who,” Not “How”

But before you make that first crosscut, you have to answer a question that has plagued craftsmen for centuries: What, exactly, are you making?

But, the crucial question isn’t just “what am I building?” but rather “what problem am I solving?” This distinction matters more than most beginners realize. Successful furniture design requires envisioning not only how something will look, but more importantly, how it will perform in real-world use. While prototyping and iteration are often necessary, especially with unfamiliar materials, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel every time.

Designing in three dimensions requires the ability to visualize how an object will eventually look and perform before you actually make it. The design process is never easy, and if you are working with unfamiliar materials, it becomes even more complex. Indeed, you may find it is often necessary to construct a series of prototypes to test every design decision.

However, even if you are a beginner, you do not have to stumble in the dark. You can draw on the experience and expertise accumulated by generations of craftsmen and designers.

Welcome to the first part of our series on Woodworking Design. We aren’t talking about joinery or finishes yet. We are starting at the very beginning: Function. Before a piece of furniture can be beautiful, it must be useful. In this comprehensive guide, we are going to explore why “Form Follows Function” isn’t just a cliché—it is the law of the workshop.

The Pressure of Originality

There’s an unrealistic expectation among new makers that every project should break new ground aesthetically. This is misguided. Furniture design has evolved gradually over centuries, shaped by material properties, technological advances, and cultural preferences rather than sudden creative breakthroughs.

Historically, most furniture makers were skilled artisans who replicated proven designs using time-tested methods. Innovation was typically reserved for high-end workshops serving wealthy patrons willing to fund experimental work. This wasn’t a limitation—it was wisdom.

But the rate of change was slow. The majority of woodworkers throughout history were artisans, rather than designers in the modern sense. They continued to make familiar objects, using the same tools, methods, and materials as their fathers and grandfathers, knowing exactly what the results would be. Only the most fashionable workshops produced innovative designs for clients wealthy enough to pay for development costs.

Here is the lesson for the modern woodworker: You could do a lot worse than to follow this example. No one wants to stifle originality, but it would be stupid to ignore a wealth of experience simply to avoid copying what has been done previously. Before attempting to break new ground, you should work to understand how your chosen material behaves and, most importantly, appreciate how the finished item is to function.

Avoid visual gimmickry. Start with the purpose.

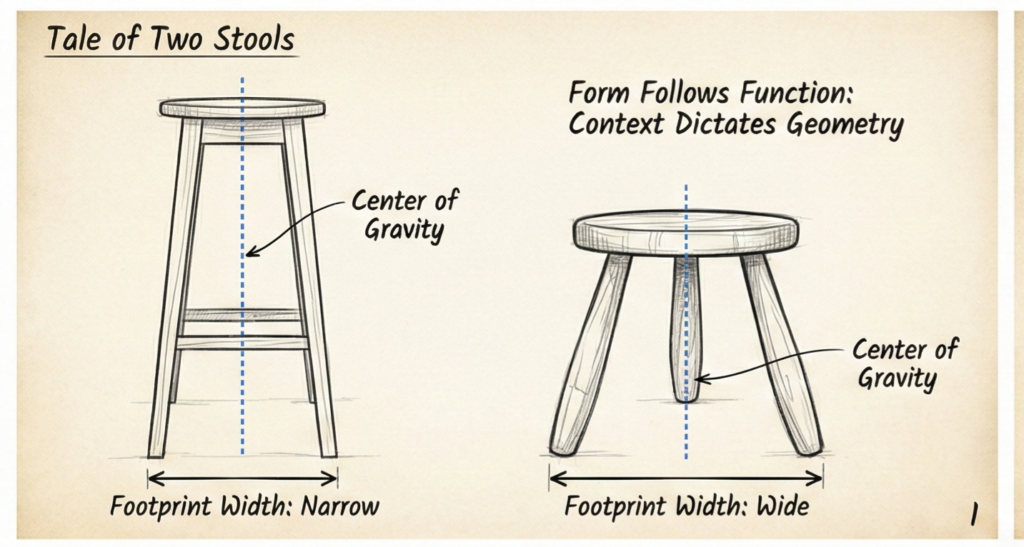

Defining “Function”: The Tale of Two Stools

Much is talked about designing for function, but to understand what that really means, we have to examine the concept from several angles.

Let’s look at the simplest example: a place to sit. A solid block of wood can function as a stool. If you are tired, and there is a stump nearby, that stump is functioning perfectly as a seat. But a well-designed stool is something else entirely.

Consider the difference between a Bar Stool and a Milking Stool.

Both objects are defined as “stools.” Both support a seated human being. Yet, they have completely different functions and, consequently, different dimensions:

- The Bar Stool: They need significant height to bring users up to counter level. This elevated center of gravity demands either splayed legs or a weighted base for stability. Since feet can’t reach the floor, some kind of footrest becomes essential for sustained comfort.

- The Milking Stool: This needs to be low to the ground to reach the animal. It needs to be lightweight so the farmer can carry it with one hand while holding a pail in the other. It usually has three legs rather than four, because three legs will never wobble on the uneven ground of a barn floor.

If you designed a milking stool with the height of a bar stool, it would tip over immediately. If you designed a bar stool with the three-legged lightness of a milking stool, it would likely collapse or feel precarious.

The Interrogation Phase

To design for function, you have to play the role of an interrogator. You must pose questions to define how an object is to function, then provide a design solution based on real requirements, as opposed to preconceptions.

Before you sketch a single line, ask yourself:

- The Environment: Should this stool be, in a public building, bolted to the ground to prevent it from being toppled and blocking a fire-escape route? Or is it for a kitchen where it needs to slide under an island?

- The Mechanics: Does height adjustment make sense? Should it fold, stack, or disassemble?

- The Stability: Will it tip easily when someone shifts their weight?

An elegant design solution is one that comes close to answering all these questions—though be warned, it will seldom, if ever, be perfect. Design is almost always a compromise.

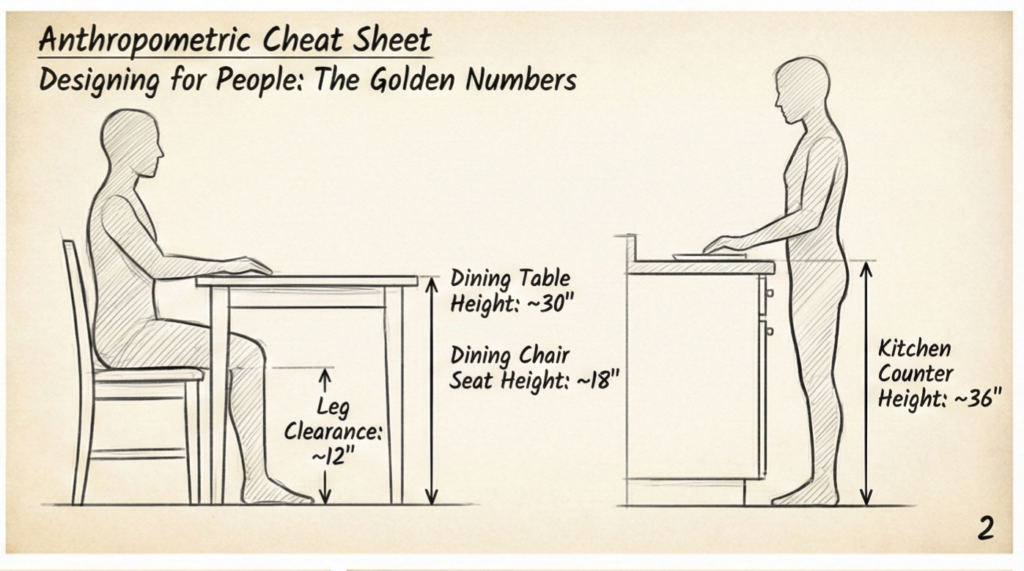

Designing for People: Anthropometry and Ergonomics

In order to be functional, most items of woodwork have to relate in some way to the human body. This is where woodworking stops being about “wood” and starts being about “biology.”

If you build a dining table that is 36 inches high, you haven’t built a dining table; you’ve built a workbench. If you build a dining chair with a seat height of 24 inches, no one will be able to fit their legs under that table.

As a species, we differ widely in size, shape, and weight. If you are designing a chair for a specific individual, you need to take careful measurements of that person’s anatomy before you can be sure the chair will be comfortable. However, for most projects, we rely on two statistical sciences:

1. Ergonomics examines how people interact with objects and spaces, focusing on efficiency and comfort.

2. Anthropometry offers comparative data on body measurements and physical capabilities across populations.

These sciences provide designers with the “optimum dimensions” for furniture and workstations that suit people of average height and build. Most people are reasonably comfortable using furniture based on these dimensions.

When to Customize vs. When to Standardize

When should you ignore the standards? If you are making something for a specific group of people, such as children or the elderly, you may have to create custom-built artifacts tailored to their needs.

The Elderly: Furniture often needs to be slightly higher and much firmer. Soft, deep sofas can be incredibly difficult for an elderly person to stand up from. Armrests become structural supports for leverage, not just places to rest an arm.

Children: Dimensions change rapidly. A desk built for a 6-year-old is useless to an 8-year-old. This leads us to our next pillar of functional design: Adaptability.

The Power of Adaptability

Adaptable designs extend useful life and maintain relevance through changing circumstances. Life is dynamic—families expand, people relocate, needs evolve. Furniture that can adapt has better odds of being retained rather than discarded.

Bunk beds that separate into standalone singles exemplify smart adaptability. They solve the immediate space constraint of children sharing rooms while remaining useful when circumstances change.

Extension tables like the traditional draw-leaf design offer another model—compact for daily use, expandable for hosting.

Adjustable shelving in bookcases or storage units accommodates unpredictable future needs better than fixed configurations.

The design question becomes: what secondary functions can this piece serve?

When designing, ask yourself: How can this piece do “double duty”?

The Aesthetics of Function

You might be thinking, “This all sounds very practical, but I want to build something beautiful.”

The beauty of woodworking often comes from the honest expression of its function. A designer should endeavor to avoid visual gimmickry. A chair doesn’t need to look like a spaceship to be a great chair. In fact, if the “spaceship” design elements make the chair uncomfortable or heavy, the design has failed, no matter how cool it looks on Instagram.

Design choices often have practical roots:

- Overhangs: A table top usually overhangs the base not just for looks, but to allow for wood expansion and to provide a place to clamp a meat grinder or a reading lamp.

- Splayed Legs: A Windsor chair has legs that angle outward. This isn’t just a stylistic choice; it physically widens the base of support, making the chair more stable without making the seat uncomfortably wide.

When you let the function dictate the form, you often find a natural, effortless beauty.

Your Design Homework

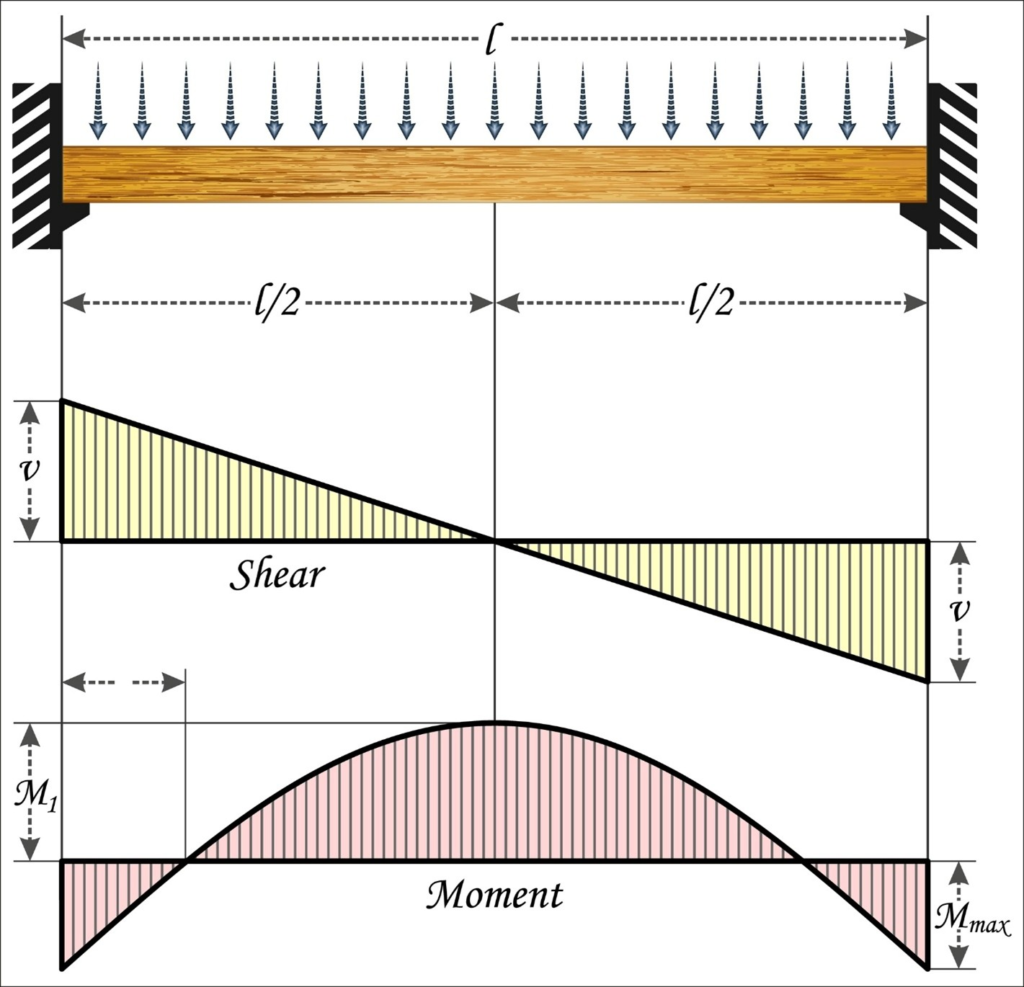

Before we move on to the next chapter of this series, where we will discuss Structure (how to keep the thing from falling down), I want you to try an exercise for your next project.

Don’t start by looking for plans online. Don’t start by drawing a shape that looks cool. Start by writing a Design Brief. Grab a notebook and answer these questions:

- Primary function: What specific task will this object perform?

- End user: Who will use it? What are their physical characteristics and limitations?

- Environment: What are the spatial, climatic, and structural conditions of its location?

- Lifecycle: What flexibility or disassembly might be needed over time?

Working through these questions transforms generic construction into purposeful design. You’re not just making furniture—you’re solving problems.

Once you have these answers, you aren’t just building a “block of wood.” You are designing a solution.